Until recently, many organisations have allowed technology to be the primary responsibility of the department, with in-house or external IT services designated for nominal support. However, the advent of AI has changed this traditional stance forever. Now the board must decide how newfound AI superpowers are best managed and implemented.

AI is already becoming embedded within some boardrooms. Directors recognise the benefits of its leverage to track the capital allocation patterns of competitors, identify opportunities for increased R&D, uncover alternative business strategies, and enter new markets with key products.

This helps keep the company several steps ahead of its rivals, offering market share growth when society faces multiple challenges leading to uncertainty across domestic, global, and geopolitical spans.

These threats range from climate change and growing cybersecurity risks through to increasing demands for social, economic, and political justice. Boards have a chance to put AI to effective use in developing new strategies that anticipate and overcome many of these elements.

Directors must take responsibility for addressing how AI is used.

However, to realise such an advantage, directors must take responsibility for addressing how AI is used. The core role of directors is to make decisions, but as decision-making is inevitably a collective exercise, this process can become overly complex. So where to begin?

Liability and corporate responsibility

Boards should be aware of one of the most critical areas impacting their future – the liability shifts through AI adoption.

The central question is, can a company unwittingly assume greater liability by using AI to enhance the usefulness of a product or service?

While ethical decision-making has always been a part of business, AI introduces a new layer of complexity.

The extent and frequency of this change in financial services remain uncertain. However, in the case of motor insurance, it is increasingly agreed that the liability for autonomous vehicles will rest with the manufacturer rather than the driver.

This is a crucial point of difference for boards to consider while navigating the evolving nature of AI. While ethical decision-making has always been a part of business, AI introduces a new layer of complexity. The fact a machine is capable of performing a task doesn’t necessarily mean it should.

There is a concern that machines may learn inappropriate behaviour from past human decisions.

To complicate matters further, AI’s advent increases an overcrowded boardroom agenda. Leaders will now have to confront ethical, accountability, transparency, and liability issues brought to the surface by new, often poorly-understood technology.

These challenges are forcing organisations to undergo significant changes.

Additionally, there is a concern that machines may learn inappropriate behaviour from past human decisions. It can be challenging to determine what is right, wrong, or just plain creepy in the era of models and algorithms.

Overseeing the ethics of AI

Overseeing AI in action creates new responsibilities and roles, making accountability anything but straightforward. The difference between right and wrong is becoming more nuanced, particularly because there is no societal agreement on what constitutes ethical AI usage.

Companies naturally strive to remain secretive and maintain a competitive edge. Nonetheless, to be at the forefront of the market organisations must be transparent when using AI. Customers need and want to know when and how machines are involved in making decisions that affect them or are being made on their behalf.

It is crucial to clearly and explicitly communicate which aspects of customers’ personal data are being used in AI systems and consent is a non-negotiable requirement.

Boards may need to be more deeply involved in determining the approach and level of detail required for transparency, which in turn will reflect the values of their organisations.

The responsibility for determining a ’sufficient’ explanation ultimately lies with the board, who must take a firm stance on what this means for themselves and other stakeholders.

Although many directors would prefer to avoid taking the risk of disagreeing with ultra-intelligent AI machines, it is crucial for board members to question the validity of black-box arguments and have the confidence to demand an explanation of how specific AI algorithms work.

—

The article is 0riginally published in Boardview 1/2023 magazine.

About the Writer

Andrew Kakabadse, Professor of Governance and Leadership, Henley Business School

Andrew has undertaken global studies spanning over 20,000 organisations (in the private, public, and third sector) and 41 countries. His research focuses on the areas of board performance, governance, leadership, and policy. He has published 45 books and over 250 scholarly articles, including bestselling books The Politics of Management, Working in Organisations, The Success Formula and Leadership Intelligence: The 5Qs. Andrew has consulted, among others, for the British, Irish, Australian, and Saudi Arabian governments, as well as Bank of America, BMW, Lufthansa, Swedish Post, and numerous other organisations. In addition, he has acted as an advisor to several UN agencies, the World Bank, charities, and health and police organisations.

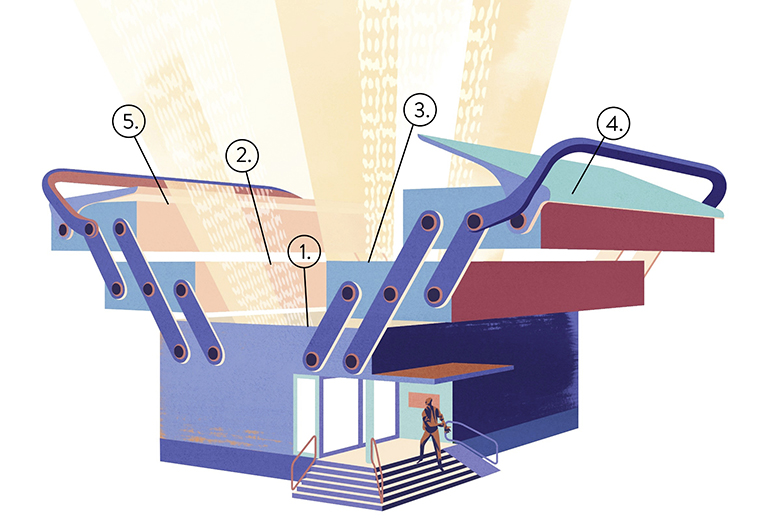

Illustration: Jussi Kaakinen