Culture has become a headline issue for companies but few seem to pay it more than lip service. How do you turn such an important issue into focused action?

Culture is one of the biggest business buzzwords of our time. A decade since the 2008 financial crisis discredited “shareholder value” as a sole justification of business action, corporations are looking inwards at the values and behaviour that defines them.

The term itself of course is hardly new. “Culture eats strategy for breakfast,” a statement denoting that corporate plans will easily be derailed if they don’t reflect the values and behaviour at a company’s heart, was attributed to consultant Peter Drucker by former Ford chief executive Mark Fields back in 2006.

Twelve years on, however, an enlightened and dynamic corporate culture is seen as enabling much more, providing an elusive connection with millennial staff and customers and becoming part of a corporation’s risk management.

Cautionary tales

Contemporary cautionary tales of companies that got culture wrong are widely evident.

At taxi-service pioneer Uber, an aggressive culture undermined its innovation and global growth and played a part in global regulators clamping down on the group.

At Barclays, following a series of scandals, former chief executive Antony Jenkins told investment bankers in 2013 to adopt new values or leave, but instead found himself ousted two years later after a disagreement over the future of the troubled division.

And most famously, a lack of an ethical culture was cited as one of the major causes of the 2001 collapse of energy trading group Enron.

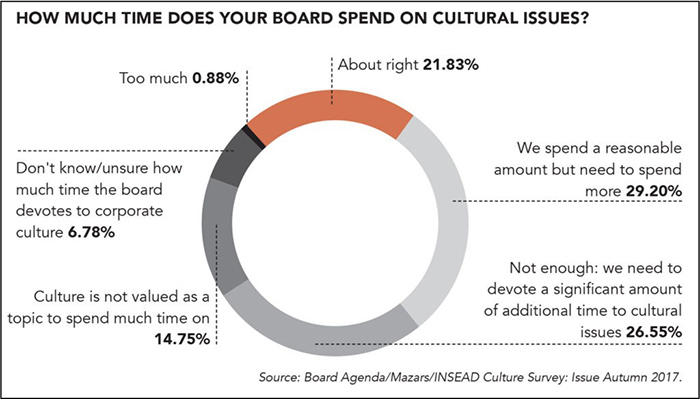

Despite the C-word gaining such currency, however, many boards are paying only lip service to it, according to Board Leadership in Corporate Culture, a Board Agenda study undertaken with professional services firm Mazars and Paris-based business school INSEAD last year.

While culture was cited as a top-three priority for company boards, only 20% of 435 directors and board members across Europe reported spending the time required to manage and improve it. Although 62% of respondents felt they were primarily responsible for setting their organisation’s culture, a similar proportion either did not consider culture as part of their formal risk assessment, or failed to routinely consider their culture’s associated risk.

Changing behaviour

Translating the recognition of corporate culture’s importance into focused action, in order to foster, encourage and shape it, is difficult because it involves changing entrenched attitudes and behaviour.

“It’s easy to train a happy worker to make coffee,” comments retail guru Mary Portas, who once sent three lacklustre shop girls to learn about the corporate culture of sandwich chain Pret a Manger. “But it’s nigh-on impossible to teach someone with a poor attitude how to greet customers cheerfully and bring a positive spirit into a store. The culture of your business is its most important thing.”

Some organisations enforce this to the point of exclusion, providing an interesting comparison with their attitudes on wider cultural inclusion.

While diversity of race, gender and sexual orientation is increasingly being accepted and encouraged, cultural dissension is becoming a dismissal offence.

“Culture is so important to us that we will only recruit people who get our culture,” says Craig Donaldson, chief executive of British retail banking newcomer Metro Bank, who admits that failure to grasp this has also led to several departures.

Kristin Furber, people director of BBC Worldwide, agrees that employee behaviour is a key focus. “It is behaviours that are going to build the culture that we want going forward,” she says.

Not just hot air

It is tempting to see such declarations as hot air and wonder whether the current obsession with corporate culture will turn out to be a fad. However, the successes of companies that built whole reputations on their culture provide inspiration for the latest crop of companies seeking to emulate them.

While diversity of race, gender and sexual orientation is increasingly being accepted and encouraged, cultural dissension is becoming a dismissal offence.

Bruno Heynen, secretary to the executive committee and governance adviser at Swiss pharmaceuticals group Novartis, cites the safety and security culture of chemical group Dupont as a major inspiration.

“We are going through a dramatic culture change,” Heynen told an International Corporate Governance Network conference in Paris late last year.

“Two years ago, our culture was all about being very performance-driven, meeting targets. But we had four departments and no co-operation with the head office. Co-operation was not part of our strategy and culture, so it required a new culture.”

Novartis’s culture change started with redefining the company’s stated 16 values, which were whittled down to six: innovation, quality, collaboration, performance, courage and integrity. Subsequently, structural changes were made to ensure that these values were given appropriate time at executive meetings and were seen to be percolating down through the organisation.

“The biggest mistake you can make,” stated Heynen, “is when you get star performers in a sales culture who are very good at reaching their targets but not that good at how they reach them.”

“Not promoting someone who is a star performer is tough but we now always consider not just whether someone is reaching their target, but how they are doing that and whether they live our new values.”

Auditing culture

Culture is traditionally seen as being hard to measure but David Herbinet, Mazars’ global head of audit, says this is not only possible but is forming an increasing part of how the firm helps its corporate clients. “You can benchmark against a target culture,” he says. “We carry out culture audits, where the methodology is very similar to a financial audit.”

Such audits assess stated purposes, values and culture against the actual progress that organisations make in asserting and following them.

“Culture eats strategy for breakfast but culture gets its appetite from purpose.”

–John O’Brien, Porter Novelli

While the Board Agenda study found that only one-quarter of boards undertake internal or external culture audits, Herbinet sees them becoming part of the auditing cycle.

Regulators are also demonstrating increased interest, with the UK’s Financial Reporting Council’s Corporate Culture and the Role of Boards report of July 2016, advising: “The strategy to achieve a company’s purpose should reflect the values and culture of the company and should not be developed in isolation.”

John O’Brien, head of purpose at consultancy Porter Novelli, agrees, going as far as to write on the back of his business card that: “Culture eats strategy for breakfast but culture gets its appetite from purpose.”

Acquiescence in this campaign from the global investment community will be crucial. However, Jean-Philippe Desmartin, head of responsible investment at Edmond De Rothschild Asset Management in France, feels that the industry is beginning to understand the importance of a strong and ethical corporate culture.

“As a family company, we have always had a long-term approach,” says Desmartin. “The financial markets are more performance-driven and short-term but there is an increased understanding of longer-term drivers too.”

Culture’s new club

The risk remains that, as the inevitable boom-and-bust cycle continues, culture and purpose will be abandoned in pursuit of shorter-term trends. However, culture’s new club of advocates believe that a heightened awareness of the importance of culture should serve as a measuring rod of intentions and reality.

“There is a danger that culture and purpose will become like sustainability as a business issue and just have rooms of manuals about them that nobody reads,” says Brian Crimmins, chief executive of One Hundred, a coalition of marketing agencies focused on non-profit organisations.

“However, there is definitely momentum behind this now,” he adds. “If companies are just paying lip service to the importance of culture in their organisations, I think they are going to get called out earlier than they may have been in the past.”

Text: Andrew Cave

The article was first published in Board Agenda